• The investment backdrop is undergoing a secular transition as many traditional anchors keep shifting or are even reversing.

• Understanding the complex trends driving this transition can provide an edge to investors in today’s changing markets.

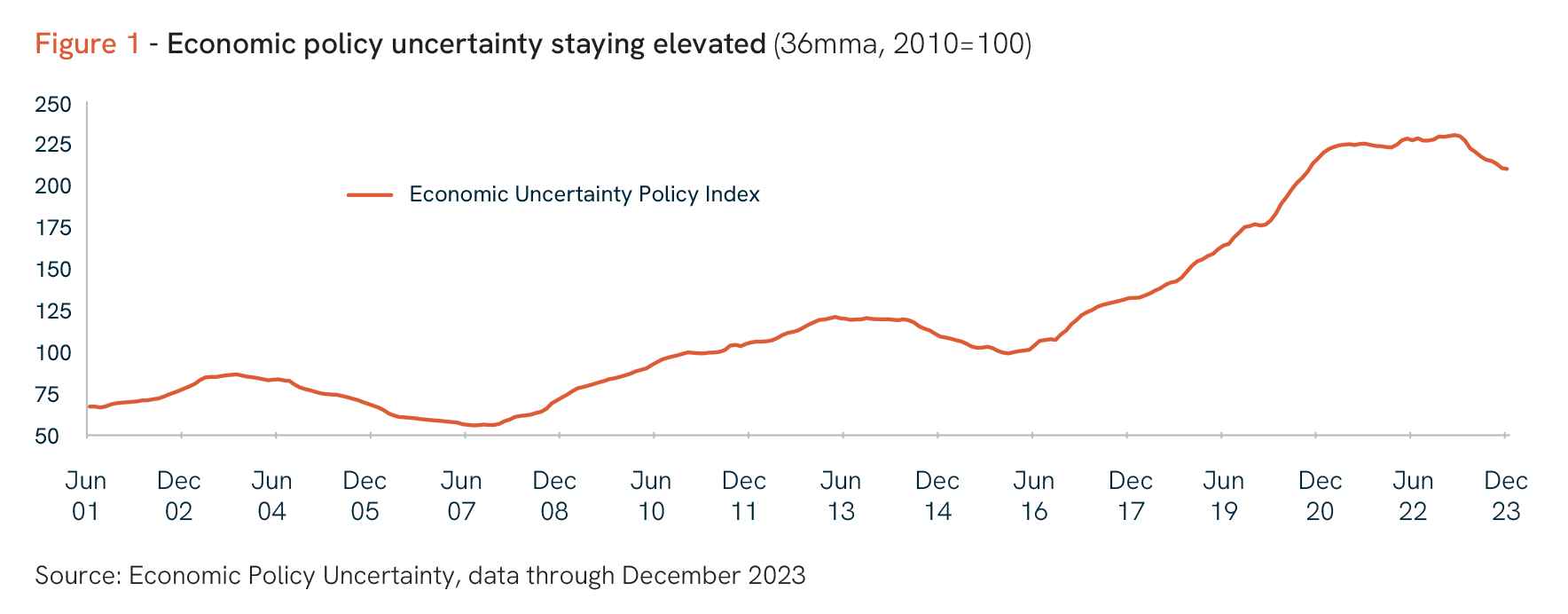

The investment landscape in emerging markets (“EM”) is undergoing a regime change as the many macro dynamics that anchored past asset allocation decisions are shifting and, in some cases, reversing. An ongoing transition to this new regime – and the durability, intensity, and evolution of the trends driving it – appears to be contributing to higher macro volatility, swings in cross-asset correlations, and a wider dispersion in returns (see Figure 1). Understanding how countries, sectors, and companies fit within these secular shifts and how they respond to them, therefore, becomes an important pillar for investment frameworks and a source of potential alpha generation.

The many forces reshaping the investment backdrop are challenging conventional narratives. As it is often the case during inflection points, some shifts may not seem immediately obvious or persistent. The market impacts are frequently masked by shocks, like the many distortions unleashed by the pandemic. The optimism about China’s post-reopening rebound was short lived, yet equities and other EM economies are performing well – a break from the past when Chinese policy and demand set the tone for the rest of EM. Moreover, EM ex-China equities rallied over the past year despite a resilient dollar and mixed commodity prices. Expectations of U.S. Federal Reserve (the “Fed”) policy remains a critical swing factor for global stocks, bonds, and currencies. Yet, a growing number of EM central banks are cutting rates, pointing to greater degrees of freedom to better calibrate policy to local conditions instead of, as was often the case in past cycles, behaving reactively to Fed actions. Partly reflecting increased local credibility, the spread between local EM and U.S. yields is near the narrowest in at least a decade (see Figure 2).

There are compelling reasons supporting the case that investors are facing a break from the past on many fronts. The end of the Great Moderation period of low, stable interest rates and inflation is giving way to today’s backdrop of higher real yields and heightened macro uncertainty. While the appropriate level for the equilibrium real rate remains a subject of intense debate, there is a wider consensus that rates will stay higher than the pre-pandemic norm. Decades of mispricing negative externalities from environmental degradation are also behind, leading to efforts to mitigate the fallout from climate change and to cut carbon emissions. The implications from aging and longer life spans are wide ranging, too. Higher levels of healthcare spending and a trend rise in green investments will act to widen government budgets over time. Finally, the adoption of artificial intelligence holds the promise of boosting productivity across industries.

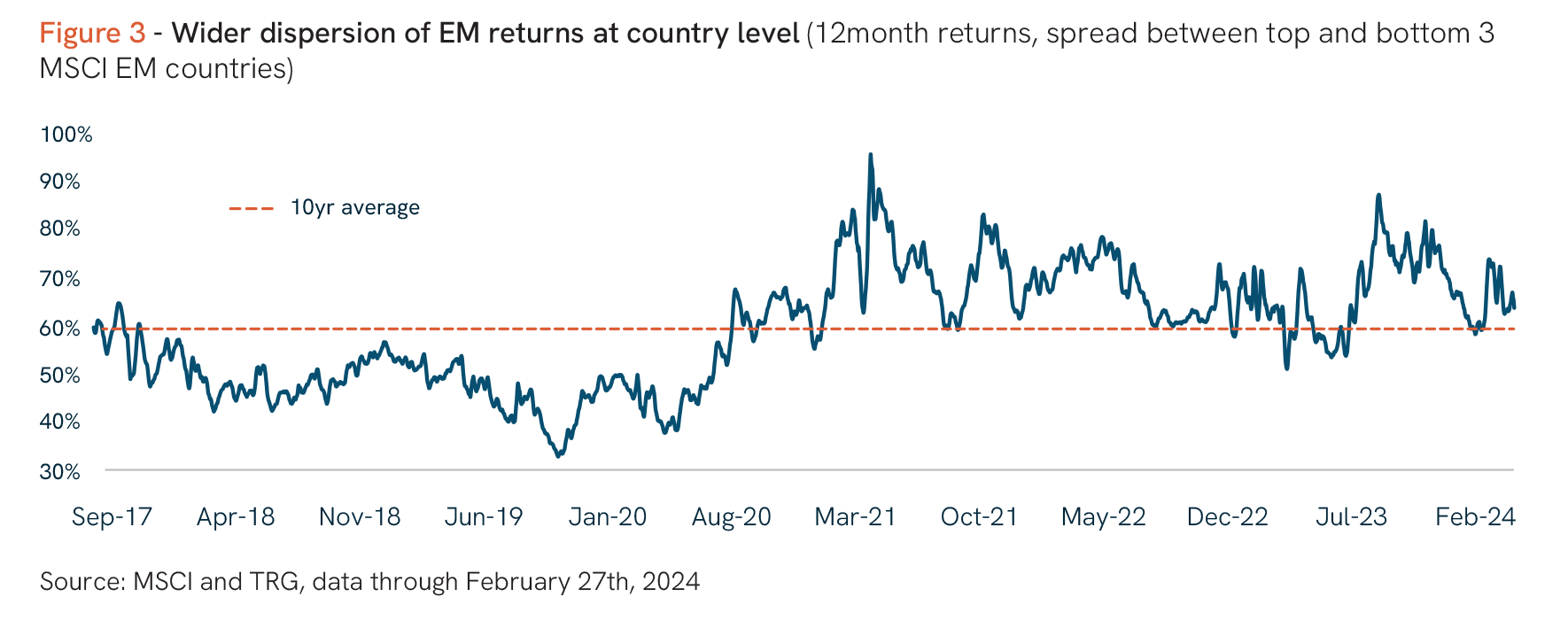

A practical framework to navigate this new regime is through changes in the traditional roles of various economic agents. One of these changes centers on monetary and fiscal policies and their ability to dampen volatility and put a floor on markets – the proverbial policy “puts.” The environment of low interest rates, inflation, and manageable debt loads that allowed for sizeable fiscal and monetary expansions to take place at a low cost is no longer present. That means policymakers face more difficult trade-offs in terms of inflation and financial stability, making them more hesitant to forcefully react to bouts of market jitters or negative shocks. For investors, it means an environment of greater macro volatility, higher risk premia, and wider dispersion of returns (see Figure 3).

An example of this more challenging balancing act for policymakers comes from the UK’s “mini budget” crisis, when the announcement of unfunded tax cuts triggered fears over fiscal sustainability, leading to a bond rout that jeopardized financial stability. Moreover, the government’s plan to support growth through the proposed fiscal expansion clashed with the Bank of England’s objective of controlling inflation, which at the time was running at a double-digit annual rate. During the 2023 regional bank crisis in the U.S., policymakers responded with targeted measures such as deposit guarantees and credit facilities; still elevated inflation, however, meant rate cuts were off the table.

The role of China as an engine of global growth and stability is also shifting. The country’s policy pivot towards self-sufficiency and national security – at the expense of growth and openness – appears to be permanent, or at least long enough to be a prudent assumption under most investment horizons. This pivot, in turn, forces investors to adjust to a structurally-slowing China that is no longer willing or able to act as a global swing factor for demand or as a source of credit (including to many frontier economies with limited market access). China’s policy response to the economy’s subpar growth pace illustrates this point. Stimulus efforts have been piecewise and measured, a far cry from the 2009-10 stimulus that topped 10% of GDP and boosted both domestic and global activity. Rather than growth, today’s policy decisions seem more influenced by the goal of maintaining financial stability by tackling the country’s heavy debt load through deleveraging of property developers and local governments.

Lastly, higher geopolitical risk is likely here to stay. The peace dividend of the past three decades anchored by unchallenged U.S. power is splintering, the trend of rising China-U.S. tensions taking its place. This “great power competition” is just the most consequential of many ongoing conflicts. Their combined impact could result in more financial and trade fragmentation, a rethink of supply chains and industrial policy, forced migration, and pressures on public finances. Europe is adjusting to the need of higher defense spending, requiring more debt, higher taxes, reprioritization of spending, or a combination of the three. The shift towards friend-and-near shoring is benefiting countries like Mexico, where machinery investment is soaring and share of U.S. imports is at record highs. This geopolitical competition goes beyond manufactured products, extending to critical commodities, too. Middle Eastern governments are increasingly redeploying their savings domestically, instead of recycling them overseas.

Adding it all together, identifying and understanding these structural trends can provide an important edge in today’s rapidly changing markets. These forces are often interrelated, self-reinforcing, and their impact on markets is complex. Countries, sectors, and companies are dealing with these trends in different ways, leading to a wider dispersion of returns and opportunities for active managers.

Relevant Reading:

Emerging Markets Navigate Global Interest Rate Volatility

by Tobias Adrian, Fabio Natalucci, Jason Wu

Have Feedback or Questions?

Contact Us:

(+1) 212 984 2900

Luis Arcentales

Luis has over 20 years of experience in covering global macroeconomics and markets. He is responsible for formulating market strategy at TRG. Prior to joining TRG, he had a short stint as an independent macro researcher following a nearly two-decade career at Morgan Stanley in New York. In his role as Senior Economist, his primary focus was developing the macroeconomic and political outlooks for countries in Latin America, in addition to publishing on topics ranging from the business cycle to trade dynamics for the region. Luis started his career as an equity strategist at McGlinn Capital, a value-oriented asset manager in Pennsylvania. He holds an MS in Economics and a BA in Industrial Engineering from Lehigh University; he sits on the board of Lehigh’s Martindale Center for the Study of Private Enterprise and is a CFA charter holder.

Vincent Low

Vincent has over 30 years of experience in covering global macroeconomics and markets. He is responsible for formulating investment ideas with PMs, strategists, and equity analysts and developing macro investment themes and processes for TRG’s public markets business. Prior to rejoining TRG, where he was previously CEO of its Singapore office and an Executive Committee member, Vincent held the role of Advisor to the Economics Policy Group at the Monetary Authority of Singapore. He also held roles as the Head of Currency and Fixed Income Strategy at Merrill Lynch, and Senior Economist for Southeast Asia at J.P. Morgan and Standard Chartered Bank. Vincent started his career at the Monetary Authority of Singapore in 1987 and received a Bachelor of Social Sciences in Economics from the National University of Singapore.

DISCLAIMER

The information provided herein is for educational and informational purposes only, and neither The Rohatyn Group nor any of its affiliates (together, “TRG”) is offering any product or service hereby. The information provided herein is not a recommendation, offer, or solicitation of an offer to buy or sell any security, commodity, or derivative, nor is it a recommendation to adopt any investment strategy or otherwise to be construed as investment advice. Any projections, market outlooks, investment outlooks or estimates included herein are forward-looking statements, are based upon certain assumptions, and should not be construed as an indication that certain circumstances or events will actually occur. Other circumstances or events that were not anticipated or considered may occur and may lead to materially different outcomes. The information provided herein should not be used as the basis for making any investment decision.

Unless otherwise noted, the views expressed in the content herein reflect those of the authors as of the date published and are not necessarily the views of TRG. In fact the views of TRG (and other asset managers) may diverge significantly from certain of the views expressed in the content herein. The views expressed in the content herein are subject to change without notice, and TRG disclaims any responsibility to furnish updated information in the event of any such change in views. Certain information contained herein has been obtained from third-party sources. While TRG deems such sources to be reliable, TRG cannot and does not warrant the information to be accurate, complete or timely, and TRG disclaims any responsibility for any loss or damage arising from reliance upon such third-party information or any other content provided herein. Exposure to emerging markets generally entails greater risks and higher volatility than exposure to well-developed markets, including significant legal, economic and political risks. The prices of emerging market exchange rates, securities and other assets are often highly volatile and movements in such prices are influenced by, among other things, interest rates, changing market supply and demand, external market forces (particularly in relation to major trading partners), trade, fiscal and monetary programs, policies of governments and international political and economic events and policies. All investments entail risks, including possible loss of principal. Past performance is not necessarily indicative of future performance.

The information provided herein is neither tax nor legal advice. You must consult with your own tax and legal advisors regarding your particular circumstances.

Our Reading List are articles that the authors believe may be interesting for people interested in learning more about emerging markets. TRG and the authors do not endorse the content of the articles and TRG and the authors may have a different view than what is contained in the article. In fact, the views of TRG and the authors may diverge significantly from the views expressed in the articles. TRG and the authors were not involved in the preparation or review of any of the articles and links are being provided merely to provide additional information about emerging markets.